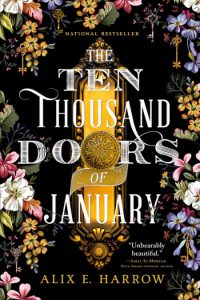

Alix E. Harrow’s debut novel, The Ten Thousand Doors of January, had been on my to-read list for a while, but I bumped it up this morning since it’s nominated for a Hugo Award. Unfortunately, I found it ultimately dissatisfying in a way that I’ll have to resort to spoilers (in a separate post) to explain.

The book did itself no favors with its opening:

When I was seven, I found a door. I suspect I should capitalize that word, so you understand I’m not talking about your garden- or common-variety door that leads reliably to a white-tiled kitchen or a bedroom closet.

When I was seven, I found a Door. There—look how tall and proud the word stands on the page now, the belly of that D like a black archway leading into white nothing. When you see that word, I imagine a little prickle of familiarity makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. You don’t know a thing about me; you can’t see me sitting at this yellow-wood desk, the salt-sweet breeze riffling these pages like a reader looking for her bookmark. You can’t see the scars that twist and knot across my skin. You don’t even know my name (it’s January Scaller; so now I suppose you do know a little something about me and I’ve ruined my point).

But you know what it means when you see the word Door.

I know I read that at least once, said "meh," and opened another book instead. If it gives you, as it did me, the impression of excessive tweeness, it is fair to say that it doesn’t carry through. This is a portal fantasy, and as is usual, also a quest fantasy, and the musings about shapes of letters recede in the face of loneliness and oppression and danger—not grimdark levels thereof, mind, but it’s not fluff either. (It remains very engaged with the power of the written word, however.)

January narrates most of the book; there’s also an interleaved manuscript for about the first two-thirds. It’s early in the 1900s in New England, and January’s father, a nonwhite man of ambiguous race, is employed by a very rich white man to retrieve "objects ‘of particular unique value.’" January’s mother died when she was a baby, so she lives her father’s employer, who successfully forces her into the mold of a "good girl" from the time she is seven until she turns seventeen, when the plot kicks into high gear.

When I finished this, my initial reaction was, "well, I appreciate populating the portal fantasy with marginalized people and gesturing at how the early 1900s sucked globally, but it doesn’t seem to be doing much with the portal fantasy besides that." Which may or may not be fair, as I’m not really up on current trends in portal fantasy; I think all I’ve read in that vein is Seanan McGuire’s Every Heart A Doorway. And a book needn’t surprise me, or be doing anything I identify as new, to be good.

But on thinking it over, the book is also—in very typical, even expected, fashion—a fantasy of political agency. And I dislike how that agency manifests in the story, because it is set in our world and is therefore making a statement that I disagree with. Ultimately, that’s my takeaway from this book, since I wasn’t in love with anything else it was doing. For more, see this post with SPOILERS.